Lee Cronin’s The Mummy Trailer Teases a Totally Different Mummy Than That Other Mummy

Jan. 12th, 2026 05:55 pmLee Cronin’s The Mummy Trailer Teases a Totally Different Mummy Than That Other Mummy

Published on January 12, 2026

Photo: Warner Bros.

Published on January 12, 2026

Photo: Warner Bros.

Published on January 12, 2026

Image: Netflix © 2025

Published on January 12, 2026

Photo: Bret Kavanaugh [via Unsplash]

Photo: Bret Kavanaugh [via Unsplash]

If you asked someone to name the main trends in genre book publishing from the past year or two, they’d probably mention romantasy, cozy fiction, horror and a few other things. But I’ve been blown away by a sleeper trend lately: novels about people storing their memories remotely, gaining access to someone else’s memories, or sharing a memory with another person. In general, memory seems to be on a lot of people’s minds lately.

Just recently, I’ve loved a ton of books on this theme. The notion of copying, storing, and sharing memories isn’t exactly new—in fact, I played with it quite a bit in my novel The City in the Middle of the Night. (Yoko Ogawa’s influential The Memory Police also deals with the ways our memories are controlled and overseen.) But this new wave of novels is using the concept to explore deep questions about personal identity, as well as the ways that our memories can be politicized and policed by repressive regimes.

To find out more about this topic, I talked to four authors of recent books that deal with this concept in various fascinating ways. (I also reviewed some books on this theme a while back for The Washington Post.)

One of my favorite books of 2025 was The Antidote, the long-awaited new novel by Karen Russell. The Antidote is the sobriquet of a prairie witch in dustbowl-era Nebraska, who acts as a sort of bank vault for people to store their unpleasant memories—with the promise that you can retrieve the memory later when you need it. But after a catastrophic dust storm, the Antidote and other prairie witches find their vaults cleaned out, all the stored memories gone forever.

The Antidote turns into an examination of buried historical trauma, especially the attempted genocide of Native Americans—thanks in part to a New Deal photographer’s magical camera that takes pictures of the past and future.

In writing The Antidote, Russell says, “I was interested in what happens when people are unable or unwilling to reckon with the past, in the exiling of memories from our waking consciousness and from our public histories, those things that many of us must continuously forget or suppress in order to go on living as we do, and how that ‘collapse of memory’ harms us individually and collectively.”

Russell adds, “I do think that whatever else a memory might be, it’s never the fullness of what happened. It’s always a (re)creation, never static or inert.” And that “these secrets that can feel so private and so personal, can become, in aggregate, something like a mass denial. Who and what we exclude from our family stories and collective histories has tremendous consequences, for all of us.”

Russell says that while she was researching the novel that became The Antidote, she learned about an astonishing act of curatorial violence. Everyone has seen the iconic Dust Bowl photographs taken by New Deal photographers like Dorothea Lange—but the architect of this program, Roy Stryker, used a hole-punch to destroy the photographic negatives he didn’t want to include, in what Russell calls “an act of artistic curation and in some cases political calculation.” Russell says there’s a “shadow archive of unpublished and hole-punched negatives,” suppressed for decades, which you can now view online at the Library of Congress.

Russell kept returning to one particular image of “a student with a hole-punched ear,” and “that hole-punched negative came to feel like the heart of this novel.”

Another book I loved in 2025, Mia Tsai’s The Memory Hunters, takes place in a world where some special people, like Key, can harvest memories from other people. Key can also unearth memories from people who lived long ago, using a complex process involving mushrooms. When Key finds an old forbidden memory that contradicts the official record and threatens the political order, she’s forced to hide it—but the memory is taking over her personality and she’s in danger of losing herself. Her bodyguard and lover, Vale, is forced to take drastic measures to save her.

Tsai says she’s always been fascinated by the concept of memory. “Memory is magic!” she says. “How can something so crucial and something we stake our lives and personalities on be so easily tampered with?” Tsai points out that a lot of books that came out in the past year were probably acquired in 2023, and written in 2020-2022, if not earlier. And there’s one thing about the early 2020s that seems especially relevant to her.

Says Tsai:

I think the wave of memory-related books has a lot to do with how we’ve been gaslit as a nation over how devastating Covid has been and continues to be (plus the global gaslighting over the genocides to which we’re daily witnesses). What we experienced and what we remember does not match up with what we’re being told. And invalidating a memory is so deeply personal. It’s hurtful and provocative to say, “No, that’s not how it went.”

The gaslighting began before Covid, of course, and the first Trump administration was already bombarding us with lies and trying to erase the very existence (and accomplishments) of marginalized communities. All this, while “burying our ability to process beneath continual outrage,” says Tsai. “In a way, sharing memories to verify their realness became a way to bond with someone else, a way to confirm that what we experienced was real, unbelievable as it was.”

Tsai sums it up perfectly: “Memory-recording lets us know we were there and it happened; memory-sharing proves we were alive and not alone.”

Recently, Tsai visited some Civil War battlegrounds, and saw a monument to Confederate general Stonewall Jackson. Nearby, there was a sign entitled, “The War Over Memory,” which detailed “one of America’s first great delusions,” or one of our earliest propaganda campaigns, “the effects of which we’re still feeling 160 years later.”

It’s not just that we’re being lied to about events that we personally witnessed, says author Seth Haddon—it’s that we have more ability to witness those events than at any other time in history, because we’re all connected. We can share the experiences of people around the world who are “enduring violence, displacement, [and] oppression.” And at the same time, mainstream and official narratives present a very different picture of reality. “This gap between lived (or viewed?) experience and official stories has made the question of memory feel newly urgent,” says Haddon.

In Haddon’s great space-opera novella Volatile Memory, a trans scavenger named Wylla finds a mask that gives her enhanced abilities—but when she wears the mask, she also experiences the memories and consciousness of the dead person who wore it before, a woman named Sable. Haddon uses the sharing of Sable’s memories to ask some deep questions about how our memories make us who we are, but also how our embodiment shapes our experience of being alive.

Haddon says that the notion of “preserving the self” is even more important when we’re under so much pressure to deny what we’re witnessing. The main way we can preserve the self is by holding on to memory, “even if it can’t be free from personal/contextual bias.” Our memories end up “feeling more intimate and trustworthy than the flood of information we receive from elsewhere, especially in a time when so many sources feel compromised.” We feel as though an individual person’s memories are “purer and more authentic” than the narrative shared by a lot of people, even if the notion of authenticity is inherently messy.

Yiming Ma’s fascinating These Memories Do Not Belong to Us takes the theme of censorship and repression to a further extent, taking place in a future dominated by a new Qin Empire, in which everybody has a Mindbank that records their memories. Some past memories are contraband, either because they have subversive themes that the government disapproves of or because they contain historical events that the government wants to cover up. Ma’s novel in stories contains a narrative assortment of forbidden memories, which the main character has inherited after the death of his mother.

Ma says that he was interested in resilience when he wrote These Memories, because it’s by having a shared narrative that we can “stay resilient and resist” during times of political turbulence. This shared narrative can come from writing that explores “both individual and collective memory.”

Ma also was inspired by the fact that researchers have continued to make a lot of new discoveries about how memories are made and stored. For example, scientists have new evidence that memories can be stored outside the brain, and that our memories are dynamic rather than static, meaning that we are constantly revising them every time we revisit them. And that long-term memories can form independently from short-term memories.

Ma was also inspired by research that reveals that some people cannot form mental images, which shows “how differently we all experience our memories and dreams.”

I was also struck by a moment in the recent novel Slow Gods by Claire North. An artificial intelligence explains that artificial minds store memories the same way humans do: by compressing them into narratives with most of the details stripped out, because the raw sensory data is too huge to store in the long term. I also found it fitting that the last book I read in 2025 was There Is No Antimemetics Division by qntm, in which monsters go around devouring people’s memories, and one particularly terrifying monster kills anyone who can remember that it exists.

What I’ve personally gotten from this recent flood of books (and what I tried to explore in The City in the Middle of the Night) is that even though we fixate on individuality—the notion that one person’s experience is totally unique—the more we can share our experiences, the more we can realize that we are one. That our fates, and our pasts, are bound together, and memory is always, on some level, collective as well as personal.

I also increasingly think that being able to experience another person’s memories is a higher form of empathy—and empathy is something we are all longing for right now, in the midst of so much performative cruelty. Not to mention community, which can only be formed by the feeling of shared heritage. (And heritage is in many ways just another word for memory.)

Says Tsai, “I don’t feel this every day, but I certainly do now: What a glory it is to continue surviving and making memories with others.”[end-mark]

This article was originally published at Happy Dancing, Charlie Jane Anders’ newsletter, available on Buttondown.

The post The Most Surprising Book Trend Right Now: Memory-Sharing appeared first on Reactor.

The MBTA welcomed Red Line riders at 7:47 a.m. with the news that a Red Line train had started pining for the fjords at Downtown Crossing, forcing the surviving trains to stand by at stations. The T reports it did what it took to clear the tracks by 8:25 a.m.

We recently received a request for a rec list of science fiction books with aro or aroace characters. Aro characters are still few and far between, but we did our best and came up with a short list of great aro scifi books! The contributors to the list are: Rascal Hartley, Alessa Riel, Adrian Harley, Shea Sullivan, E. C.

Want to request a rec list from us? You can do that! Drop us an ask on Tumblr!

Dear Stupid Penpal by Rascal Hartley

Atticus “Finch” Davani does not want to be an astronaut. He hates space, he hates the ship, and he strongly dislikes his fellow crew members. He makes that painfully clear in his letters to Aku, his corporate-assigned penpal back on Earth.

Firebreak by Nicole Kornher-Stace

“Twenty minutes to power curfew, and my kill counter’s stalled at eight hundred eighty-seven while I’ve been standing here like an idiot. My health bar is flashing ominously, but I’m down to four heal patches, and I have to be smart.”

New Liberty City, 2134.

Two corporations have replaced the US, splitting the country’s remaining forty-five states (five have been submerged under the ocean) between them: Stellaxis Innovations and Greenleaf. There are nine supercities within the continental US, and New Liberty City is the only amalgamated city split between the two megacorps, and thus at a perpetual state of civil war as the feeds broadcast the atrocities committed by each side.

Here, Mallory streams Stellaxis’s wargame SecOps on BestLife, spending more time jacked in than in the world just to eke out a hardscrabble living from tips. When a chance encounter with one of the game’s rare super-soldiers leads to a side job for Mal–looking to link an actual missing girl to one of the SecOps characters. Mal’s sudden burst in online fame rivals her deepening fear of what she is uncovering about BestLife’s developer, and puts her in the kind of danger she’s only experienced through her avatar.

Màgòdiz by Gabe Calderón

Màgòdiz (Anishinabemowin, Algonquin dialect): a person who refuses allegiance to, resists, or rises in arms against the government or ruler of their country. Everything that was green and good is gone, scorched away by a war that no one living remembers. The small surviving human population scavenges to get by; they cannot read or write and lack the tools or knowledge to rebuild. The only ones with any power are the mindless Enforcers, controlled by the Madjideye, a faceless, formless spiritual entity that has infiltrated the world to subjugate the human population.

A’tugwewinu is the last survivor of the Andwànikàdjigan. On the run from the Madjideye with her lover, Bèl, a descendant of the Warrior Nation, they seek to share what the world has forgotten: stories. In Pasakamate, both Shkitagen, the firekeeper of his generation, and his life’s heart, Nitàwesì, whose hands mend bones and cure sickness, attempt to find a home where they can raise children in peace, without fear of slavers or rising waters. In Zhōng yang, Riordan wheels around just fine, leading xir gang of misfits in hopes of surviving until the next meal. However, Elite Enforcer H-09761 (Yun Seo, who was abducted as a child, then tortured and brainwashed into servitude) is determined to arrest Riordan for theft of resources and will stop at nothing to bring xir to the Madjideye. In a ruined world, six people collide, discovering family and foe, navigating friendship and love, and reclaiming the sacredness of the gifts they carry.With themes of resistance, of ceremony as the conduit between realms, and of transcending gender, Màgòdiz is a powerful and visionary reclamation that Two-Spirit people always have and always will be vital to the cultural and spiritual legacy of their communities.

All Systems Red (Murderbot Diaries series) by Martha Wells

In a corporate-dominated spacefaring future, planetary missions must be approved and supplied by the Company. Exploratory teams are accompanied by Company-supplied security androids, for their own safety.

But in a society where contracts are awarded to the lowest bidder, safety isn’t a primary concern.

On a distant planet, a team of scientists are conducting surface tests, shadowed by their Company-supplied ‘droid — a self-aware SecUnit that has hacked its own governor module, and refers to itself (though never out loud) as “Murderbot.” Scornful of humans, all it really wants is to be left alone long enough to figure out who it is.

But when a neighboring mission goes dark, it’s up to the scientists and their Murderbot to get to the truth.

The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet by Becky Chambers

Rosemary Harper doesn’t expect much when she joins the crew of the aging Wayfarer. While the patched-up ship has seen better days, it offers her a bed, a chance to explore the far-off corners of the galaxy, and most importantly, some distance from her past. An introspective young woman who learned early to keep to herself, she’s never met anyone remotely like the ship’s diverse crew, including Sissix, the exotic reptilian pilot, chatty engineers Kizzy and Jenks who keep the ship running, and Ashby, their noble captain.

Life aboard the Wayfarer is chaotic and crazy—exactly what Rosemary wants. It’s also about to get extremely dangerous when the crew is offered the job of a lifetime. Tunneling wormholes through space to a distant planet is definitely lucrative and will keep them comfortable for years. But risking her life wasn’t part of the plan. In the far reaches of deep space, the tiny Wayfarer crew will confront a host of unexpected mishaps and thrilling adventures that force them to depend on each other. To survive, Rosemary’s got to learn how to rely on this assortment of oddballs—an experience that teaches her about love and trust, and that having a family isn’t necessarily the worst thing in the universe.

Record of a Spaceborn Few by Becky Chambers

Hundreds of years ago, the last humans left Earth. After centuries wandering empty space, humanity was welcomed – mostly – by the species that govern the Milky Way, and their generational journey came to an end.

But this is old history. Today, the Exodus Fleet is a living relic, a place many are from but few outsiders have seen. When a disaster rocks this already fragile community, those Exodans who have not yet left for alien cities struggle to find their way in an uncertain future. Among them are a mother, a young apprentice, an alien academic, a caretaker for the dead, a man searching for a place to belong, and an archivist, who ensures no one’s story is forgotten. Each has their own voice, but all seek answers to inescapable questions:

Why remain among the stars when there are habitable worlds within reach? And what is the purpose of a ship that has reached its destination?

Find these and other books on our Goodreads book shelf or buy them through the Duck Prints Press Bookshop.org affiliate page.

Join our Book Lover’s Discord server to chat books, fandom, and more!

Looking for some queer book recs? Feel free to drop us a Tumblr ask and let us know!

Published on January 12, 2026

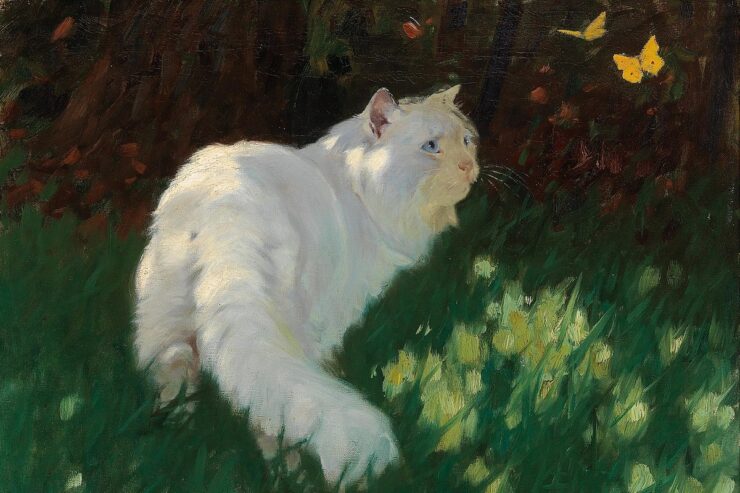

“White Cat and Butterflies” by Arthur Heyer (1914)

“White Cat and Butterflies” by Arthur Heyer (1914)

Humans have a thing for companion animals. If it’s alive, breathing, and a human can live with or adjacent to it, swim with it, fly with it, and above all connect with it, someone has probably tried. But logistically and practically, it comes down to the big three: horse, dog, and cat.

The horse is not, as a species, amenable to curling up in the house by the fire. That job is more suited to the dog and the cat. I’ll leave the dog for another day; for now, let’s focus on the cat.

Here is a small furry predator, around ten pounds (4kg) on the average. It’s a mammal like us. It walks on four paws with retractable claws, and true to its nature and heritage, it has sharp fangs. It has a long tail which it uses for balance and to express opinions. It’s quick and reactive. Its eyes are large, round, and slit-pupiled, and reflect light: eyes that can see well in low light, especially the light of dawn and dusk, when it’s most active.

It pings a number of human awwww reflexes. Soft fur, deceptively soft paws, round head and ears that activate the aww cute baby module, little squeaky voice, and the coup de grace: it purrs. Its tropism toward warmth and comfort puts it in a human lap more often than not. It’s small enough to be portable, big enough to be useful as an eliminator of vermin around human habitations (which is probably how it ended up as a companion animal in the first place).

It is not, however, harmless. Cats are poised right on the edge between tame and feral. If they’re not socialized to humans as young kittens, the feral takes over. They’re as wild as a fox or a raccoon, and in some ways more dangerous, because humans don’t always realize how effective a cat’s armament is.

That little ten-pound fuzzy thing can rip a human to shreds with its claws. It’s fast, furious, and absolutely merciless to anything that tries to hold or trap it. Cat rescues handle ferals with Kevlar gloves.

Even a socialized cat has a threshold beyond which a human can’t safely go. Stay on the right side of it and you’ve got a lovely soft purry cuddlebug. Smart humans know what happens if they push their luck.

That’s part of the allure. That edge of danger. The sense that you’re sharing your house and your sleeping place with an animal that can seriously hurt you, but chooses not to. Chooses instead to grace you with its presence, its personality, and its purr.

Humans are storytellers by nature. We make sense of the world by turning it into narrative. We perceive and create patterns. We construct explanations. We invented science to anchor those explanations to the observed and observable world, but before science was story.

In one story, the cat is divine. She’s a goddess; a mystical power. In another, she’s a manifestation of evil. A demon, a creature of the darkness. In yet another, she’s the reason for the existence of the internet, which is, we’re assured, made of cats.

Cat magic is old and powerful, but it’s not only fantasy that celebrates the cat. Science fiction has its own lore of the feline, both the original domestic cat and the felinoid alien. Science fiction authors are well known for their affinity with the species, from Robert Heinlein and Andre Norton and C.J. Cherryh to many a more modern talent. It’s an article of faith in the genre that a writer should, if at all possible, have a Writer’s Cat. Or two. Or three.

Yes, yes, I know many who have Writers’ Dogs instead or too, and then there’s the SFWA Cavalry of song and story, where the horsefolk are. But cats are a mainstay.

I’m starting this chapter of the Bestiary with science fiction because I want to. That’s how a cat does it. A cat makes her own decisions. You can persuade her, but if you try to force her, you’ll need those Kevlar gloves.

Because I want to, and because it’s a roaring good story, I’ll be starting with C.J. Cherryh’s The Pride of Chanur. Do join me in the reread (or the read if it’s new to you), and let me know what else, either written or film, you’d like to see. Especially if it’s been published or aired in this century, and better yet, within the past decade. I’d love to know about newer science-fictional cats and their attendant humans.[end-mark]

The post The Magical, Mystical, Fantastical Cat appeared first on Reactor.

That piece about people having AI spouses is online: As synthetic personas become an increasingly normal part of life, meet the people falling for their chatbot lovers.

NB we note that 'Lamar' says that the breaking point with his actual, RL, girlfriend was when he found her doing the horizontal tango with his best friend, but it's clear that there were Problems already there, about having to relate to another human bean who was not always brightly sunshiny positively reinforcing him....

what would he tell his kids? “I’d tell them that humans aren’t really people who can be trusted …

This is not entirely 'wow, startling news' to Ye Hystorianne of Sexxe: The Phenomenon of ‘Bud Sex’ Between Straight Rural Men.

I am not going to see if I actually have a copy of the work on my shelves, or if I perused it in a library somewhere, but didn't that notorious work of 'participant observation' sociology, Tearoom Trade argue that many of his subjects were not defining themselves as 'homosexual'.

I also invoke, even further back, Helen Smith's Masculinity, Class and Same-Sex Desire in Industrial England, 1895-1957 about men 'messing about' with other men in Yorkshire industrial cities.

And there is a reason people working on the epidemiology and prevention of STIs use the acronym 'MSM' - men who have sex with men - for the significant population at risk who do not identify as gay.

I had, I must admit, a very plus ca change moment when I idly picked up Katharine Whitehorn's Roundabout (1962), and found the piece she wrote on marriage bureaux. In which she mentioned that the two bureaux she interviewed tried to get their subscribers not to be too ultra-specific in their demands - that if they met potential partners in real life they would be more flexible.

Was also amused by the statement that 'Men over thirty are always very anxious to persuade me that they could have all they women they liked, if they bothered'.

Get a load of those nums, parked outside a Suffolk dorm.

A bitter resident filed a 311 complaint this morning about a food-delivery truck blocking the bus stop across from the Old State House:

Delivery truck fully blocked the bus stop because college babies need their num nums delivered.

WCVB reports on a fight - in the stands - during Saturday's Bruins/Rangers match that ended with the alleged aggressor getting shoved down some stairs and suffering what police said were serious but not life-threatening injuries.

Aaron Tucker, 48, was scheduled for arraignment in Boston Municipal Court today on charges of assault and battery and assault and battery on a person over 60 causing injury, court records show.

Innocent, etc.

The Huntington News gives us a tour of the Toussaint Louverture Cultural Center, 131 Beverly St., near North Station, which opened in May.

Published on January 12, 2026

Credit: Netflix

Published on January 12, 2026

Photo Credit: Michael Gibson/Paramount+